What we must do to supercharge European productivity

The existing venture capital model must be expanded on to support the European innovators of the future

To Vince, Tomaso, Lydia, Antoine, Ata, Mandya, Marco, Melisa, Antoni, Pietro, and little Emi who deserve a system as dynamic as you all are

If you live in Western Europe and are under 30, you should not expect to have a better standard of living than your parents. That is, unless the economic status quo is seriously reformed.

Since 2000, real per capita disposable income in the US has grown 2x faster than the EU’s. Europe’s share of (decreasing) world trade is falling and its labor productivity rate, which was once nearly on par with the US, is now below 80% of its figure.

China can no longer be counted on as a growth market for European exports. Its own industry has become capable of satisfying domestic demand. Simultaneously, Chinese companies have become much more competitive with European suppliers in global markets; they compete in 40% of all sectors, up from 25% in 2002.

Without a meaningful rise in productivity, Europe will not only be uncompetitive but also forced to abandon its fundamental values. There simply won’t be enough money to support their preservation (i.e. afford social services, lead in decarbonization, and provide for its security).

I have lived in Berlin for five years now, making frequent trips across the continent, and have seen first-hand how the mask is falling. Clever, curious, and inventive people are abundant. The tragedy is that the system is failing them by not creating the conditions to leverage their innate dynamism and be as productive as they can be.

The Draghi Report is full of astute observations and useful recommendations on the macro-institutional level, focusing on how to make the European economy more productive. Today, for this article, I will focus narrowly on one key mechanism: capital for financing innovation.

The truth is we can’t wait for government to change. Unfortunately, a bias towards inaction is the clear precedent, as explained rather tragically by Arnaud Bertrand.

If we want truly innovative companies founded in Europe that make the population more productive, we must change how investment flows within our tech sector.

I wrote years ago about how the story of tech in Europe’s largest economy has focused mostly on consumer products (B2C) and e-commerce. The Samwer brothers, Europe’s most infamous entrepreneurial family, got their start by copying eBay and selling the company ‘back’ to them after 100 days of operation for ~$50 million in the early 2000s. They then ran this playbook back with MyCityDeal, a copycat of Groupon, a few years later, netting $170 million when they sold the firm to the Chicago-based original. The brothers then founded Rocket Internet to repeat this scheme in as many markets and with as many businesses as they could.

Nakedly, the Samwers were interested in enriching themselves. There was not even lip service to the idea that their ventures might make their fellow Europeans more productive or wealthier; they were after making it easier for consumers to spend their money, often on things they didn’t necessarily need.

“The main reason EU productivity diverged from the US in the mid-1990s was Europe’s failure to capitalize on the first digital revolution led by the internet – both in terms of generating new tech companies and diffusing digital tech into the economy.” - Draghi Report, Page 20The German ecosystem blossomed from Rocket Internet seeds. Many VCs at the leading early stage funds, such as Cherry Ventures (AUM: €500m), HV (AUM: €2bn), and Project A (AUM: €850m) saw early career success at Rocket companies or their offshoots.

While these firms have been operating for some 10+ years now and naturally have evolved their focus to invest in other sectors as well, the fact remains that their biggest exits have been largely with firms that sell physical products online to consumers.

These funds and their general partners have done their jobs, assessing the opportunities in front of them and making bets on those that might deliver strong returns. They fulfilled their responsibilities to limited partners and some have even taken the uncertain step of moving outside of their comfort zones to invest in areas with more uncertain return profiles (thinking about Project A’s defence investments!).

“Europe’s lack of industrial dynamism owes in large part to weaknesses along the “innovation lifecycle” that prevent new sectors and challengers from emerging.” - Draghi Report, Page 24 In the context of the Draghi Report, however, I believe it is fair to question if the ecosystem is currently set up to funnel capital into commercializing innovations that increase European productivity, rather than to enrich a small inner circle of founders and investors.

The (perhaps inconvenient) truth is that the spiritual legacy of The Samwers and Rocket Internet largely lives on. The ecosystem came into being, for the most part, not to commercialize innovation, as it did in Silicon Valley in the 1960s, but rather as a cash grab by business school graduates who otherwise would have been MBB consultants. Today, these same folks are calling the shots at the most cash-flush VC funds.

These big funds receive the lion’s share of press, interest from potential limited partners (LPs), and access to the most hyped deals. Yet, at best, it is inconclusive to say that the existing paradigm of investors have financed (successful) ventures that have increased European dynamism, productivity, and competitiveness. At worst, it does not look like this at all.

Europeans of all stripes love to comment on the ‘infamous’ social inequality of the country of my birth. But the sad irony is that the wealth distribution across European Tech is massively concentrated amongst a tiny group of investors and executives.

Sure, in Silicon Valley you have your fair share of billionaire venture capitalists. The Andreesens, the Leones, the Conways. But, at the same time, there are also many thousands of people who have worked as employees at startups that have made millions, subsequently gaining financial security for their families.

Meanwhile, in Europe, a few dozen investors, founders, and privileged executives have seen their net worth swell into the eight or nine figures, mostly by commercializing already existing innovation from abroad or finding new ways to sell physical stuff online.

Johnny Boufarhat, founder of COVID darling Hopin, is perhaps the most egregious example of this; he cashed out for $200 million in secondary sales and two years later, the entire company was liquidated for $50 million.

Only a few employees of European startups have become seriously wealthy.

Stock-based compensation in Europe is less aggressive than in The States, mostly for tax reasons outside the control of ecosystem participants (Christian Miele has gallantly been pushing for reform here for years). European startups don’t really IPO, so liquidity events happen via secondary markets or acquisitions, which typically favor investors and executives. Most of the smaller scale M&A in Europe is a consolidation play, with local players merging to create scale but this doesn’t really make anyone rich, especially small shareholders. And, simply put, startup employees based in the EU just don’t receive much compensation to begin with.

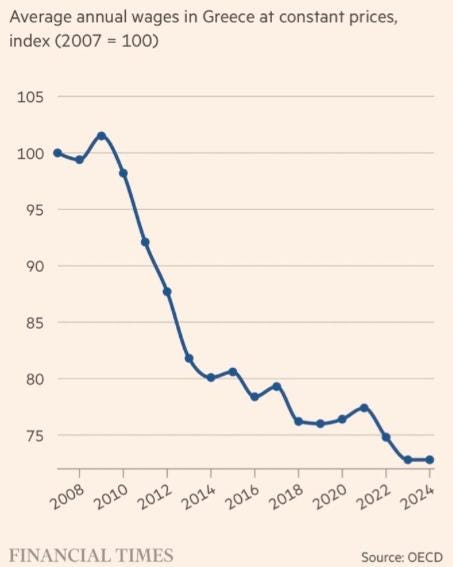

Obviously, as Draghi makes abundantly clear in his report, the citizens of Europe are not becoming wealthier or more productive either. In fact, by some measures, many are worse off (see also the UK) than 15-20 years ago.

The challenges are many, to build a more dynamic and productive economy in Europe. The continent’s struggles do not all fall at the feet of its cohort of venture capitalists. Nonetheless, the existing model for financing innovation must be expanded upon if we are going to reach the necessary objectives set out in the Draghi Report.

The European technology investment ecosystem, as is, is more focused on enriching its capital holders than it is on delivering productivity to the continent via commercializing useful innovation. We have no option but to change this if we want the children of today and tomorrow to enjoy a stable quality of life.

“The investment share in Europe will have to rise by around 5 percentage points of GDP to levels last seen in the 1960s and 70s. This is unprecedented: for comparison, the additional investments provided by the Marshall Plan between 1948-51 amounted to around 1-2% of GDP annually.” - Draghi Report, Page 1Europe needs a ‘Second Marshall Plan’ if it is serious about working towards the targets of increasing productivity, decarbonizing, and defending itself.

Capital should flow from the US, through European intermediaries like Funds-of-Funds (FoFs), and into the coffers of investment funds run by bona fide technologists with mandates to increase European prosperity writ large. Allow me to explain why.

The United States is the richest country in our planet’s history and has the world’s deepest and most sophisticated financial markets. A strong, prosperous Europe that can defend itself, wean itself off of Russian energy and Chinese clean tech, and develop technologies that benefit mankind is very much in the American strategic interest.

As has been the case for nearly a decade now, American corporations and investment funds have more money than they know what to do with. The HBR reports, for example, that non-banking US firms are sitting on $6.9 trillion in cash, larger than the GDP of all but two countries worldwide. The global PE industry has $2.6 trillion in dry powder to deploy, according to The Economist, with most of that capital coming from American sources.

Meanwhile, per the Draghi Report, the EU has a $300 billion R&D spending gap it needs to fill to reach parity with the US. And to hit Draghi’s headline figure of $900 billion to completely transform the European economy, investment must rise by around 5% of GDP.

Some of the transformation capital will come from Europe. Anticipating protests from free markets-loving California Libertarians, the report lays down the expectation that only 20% of the required investment outlay will come from public sources.

But what of the rest?

Europe is in need of massive capital deployment into innovation projects at their earliest stages. Domestic investment funds should look towards the US, where all that cash is sitting around, for funding. The issue, however, is that those who would make the best use of the money likely don’t have market access. And those that do, such as the funds with over €500m in AUM, have unconvincing track records of investing in dynamic new technologies that can move the needle on productivity and competitiveness.

What we need is a new type of financial organization. One that pairs knowledge of the micro/deeptech VC landscape in Europe with deep connections to American capital. One that can channel capital towards managers who have a mandate to back entrepreneurs figuring out how to make Europeans more productive and competitive with technology. One that can articulate the case to American capital holders for why such an undertaking is in both their financial and strategic interests.

The Draghi Report lays out with heroic clarity and perspicacity that significant changes are needed in Europe’s innovation economy to arrest declining productivity and make Europe competitive again. There is a need for almost $1 trillion in new investment to keep European living standards constant in the face of competitive pressures from China and the US, security threats, and constraints around energy resources.

Deploying the required capital likely requires a re-think of how we in Europe finance innovation. Especially because the jury is still out on whether incumbent VCs nominally focused on financing breakthrough tech in Europe are truly fulfilling their mandates.

There are trillions of dollars in the United States looking to be allocated more effectively. If Europe’s inventors could have access to only a small fraction of that money, it likely could move the needle towards delivering innovations that can meaningfully increase European competitiveness and productivity.

Specialists who have access to American capital markets, deep knowledge of the European frontier technology landscape, and are aware of the regulatory environment are crucial to bridge the understanding gap and channel capital towards strategically important projects.

Fund-of-Funds (FoFs), who pool capital from both domestic and foreign sources to identify emerging managers, are best positioned to steer the coming European innovation wave. However, they remain too quiet. FoFs structurally make venture capital more attractive for institutional investors due to their larger portfolio size and returns from emerging managers have historically outperformed those of incumbents.

FoFs should lead the charge in this new investment paradigm by funding genuine innovation. Besides having the mission to move money from where it’s abundant to where it’s necessary, they have the responsibility to educate and communicate a better ecosystem into being.

Let’s get to work!

This is exactly why we started Lunar.vc.

Back in 2016, I moved to Berlin because it was being hyped as Europe’s top tech ecosystem. What I found, though, was exactly what you described — a startup scene shaped by the Samwers’ model of success, where the focus was all wrong when it came to technical startups.

The gap was clear from the beginning. In Tel Aviv, where I grew up, founders were constantly frustrated that VCs only cared about patents, tech moats, and quick exits to the US — ignoring current revenues and overlooking opportunities to build local giants. In Berlin, every founder I met complained that VCs were obsessed with ARR and crunched rear-view-mirror numbers. They had little to no interest in the tech itself, focusing instead on ‘technology-enabled’ businesses with a quick return.

This disconnect was so frustrating that I partnered with a CTO and a computer scientist to start Lunar.vc — a firm that actually understands technology. Since then, we’ve brought into VC mostly the technical experts VCs often lack — software developers, PhDs in biology and chemistry, and entrepreneurs who’ve been in the trenches.

This is good content - consider adding some info about yourself because even after searching I'm not sure who you (the author) are :)

Happy to recommend your Substack!